Yesterday I finished the first volume of Iain McGilchrist's The Matter With Things: our brains, our delusions and the unmaking of the world; so I am about 2/3 the way through what is quite possibly the biggest book I have ever read. I do own bigger books - Kittel's Theological Wordbook of the New Testament, for example, and The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, but to be honest I've never read them. Occasionally, when necessary, I've dipped into them, in an eyes glazed over kind of way, but I'm not going to sit down, by the fire with them in the expectation of growth and expansion and delight, as I find myself doing with The Matter With Things. I'm reading it. Every word of it. Slowly. Taking breaks to think about it. Texting Eric Kyte, who's also reading it, to see if he wants to meet, yet again, to share coffee and responses to the book.

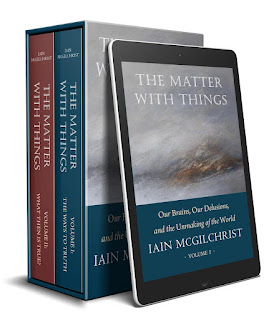

Iain McGilchrist is a polymath. He read English at New College Oxford, published a well received book on literary criticism, several other papers and monographs, and then retrained as a medical doctor and a psychiatrist. He has been a research fellow in neuroimaging at John Hopkins University and is a fellow of All Souls College Oxford. In 2009 he published The Master and His Emissary, a book on the hemispheric theory of neuroscience which received widespread academic, popular and literary acclaim. I read TMAHE and was astonished by it. A good book is one that has explanatory power; that is, it gives words to thoughts and intuitions you have always believed to be true. A good book helps to define and shape your universe and in doing so, define and shape yourself, so The Master and His Emissary was a good book for me: one of the best I've ever read. So this year when I learned that Iain McGilchrist had written another, and by all accounts even more important book, and when Clemency was asking what I might like for my birthday my answer to her was unequivocal. I even did the ordering on her behalf. It was a generous gift - the purchase price is around $250. ( the Kindle version is about $65 )

The Book Depository managed to have it on my front porch a few days after I became on old fogey. McGilchrist is, apparently, something of a perfectionist, and this shows in the production values of the book. It is printed in a clear, pure font on thick white paper, stitched and bound properly in stiff boards. It runs to 1578 pages, including appendices and the most extensive bibliography I've ever seen. Footnotes are artistically arranged down the wide margins and there are a number of illustrative plates. It is huge: the physical weight of it makes reading tricky at times, but that's Ok because I have to stop every so often anyway, to have a wee think about things.

There are three parts to the book: The Hemispheres and The Means to Truth; The Hemispheres and The Paths to Truth; and The Unforseen Nature of Reality. Volume one contains the first two parts, Volume 2 the third part and the various addenda. It is centred, as I expected it would be, around the hemispheric theory. That is, the theory (well attested and exhaustively referenced in both this book and TMAHE ) that our brains are neatly divided into two distinct hemisphers for a reason: we effectively have two brains, responsible for two different manners of perception, and these are coordinated by a comparatively slim organ called the corpus callosum. There is a wealth of pop psychology built around the concept of the Left and the Right brains, but McGilchrist's exposition of this divide is at once more convincing, more exhaustive and more subtle than the self help workshops suggest. The division in our brains is not so much about specific tasks done by each side of the brain (although there are a few of those) but about how each side of the brain pays attention, the way each side of the brain processes information, and how each side contributes to building the unique world we inhabit.

For this book is about how the world is built. It is about our knowing, certainly, but about far more than that. It is a theory of knowledge and a theory of how the universe exists. McGilchrist espouses a theory not dissimilar to David Whyte's concept of the 'Conversational Nature of Reality'. That is, we shape the world we inhabit, not as some kind of imaginary projection, but as a response to a reality which is encountered sensually. We shape that reality and that reality shapes us and we are one with that reality. The structure of our brains influences how we perceive the universe and therefore is foundational to the universe we create. This is a book about Truth: how we perceive Truth, how we process Truth, and the universe we each, truly, create and inhabit.

For a book which is so well referenced and so rigorously researched it is eminently readable. McGilchrist's eclectic range of interests, his ability to analyse and synthesise, his high level of literary skill, his sheer intelligence and his position as someone not earning his money as an academic all contribute to make this a powerful and persuasive work. The explanatory power of this book has been, for me, profound and deeply personal.

There is a shape to our lives, the one which Soren Kierkegaard is popularly misquoted as saying we live forwards but understand backwards. The shape of my life is slowly revealed, like Shrek's, in layers. And layer by gradual layer, in the things that were arising from my practice of silence, at exactly the right time, when some powerful issues were preoccupying me, I was led to (Oh, how often does this happen!) the perfect book. This one. I'm not going to go into detail here - that is the stuff I'll reserve for conversations with people whose eyes I can see while I'm talking - but in brief:

My father was mentally ill, but the diagnosis of his illness always eluded me. No longer. I'm now pretty certain, from this book and from snippets of family history and from memory, what was wrong with him. This is the occasion for vast relief, and some forgiveness.

My father was the one who was primarily responsible for teaching me how to be in the world. I always knew I was badly taught, but now have some understanding of the architecture of the misinformation which formed me. And, in unravelling a convoluted knot it certainly helps to have a free end to begin with.

And apart from my personal pathology, in piecing together the truth of the universe, over the last few decades, there are things I have always had trouble with: Scientism, for example, which is not so much the scientific method as the scientific method's dogmatic, half brained younger brother; academia with it's endless production of people who know more and more about less and less and whose vocational lives depend on producing unreadable books and papers couched in the bizarre dialect which is the lingua franca of that particular enclosed professional system; the management model with its penchant for quantifying stuff and for little graphs and five year plans (honestly, has anything of any worth ever come out of a five year plan?) and mission statements and goal setting workshops, and people with data projectors and a couple of trendy ideas; people whose impeccable logic provides incontrovertible proof of things you know to be complete bollocks (such as that the world is flat, or that consciousness doesn't exist, or that the world doesn't exist, or that life is produced by selfish genes, or any one of a number of other current fashionable tropes). These and many others besides, are carefully, wonderfully, examined by McGilchrist, and not so much rubbished as exposed and gently put in their proper place.

And in piecing together the universe there are things which have fed me. Narrative. The wonderful paradoxes of physics. The rich tradition of Christian contemplation, particularly The Cloud of Unknowing. The extraordinary phenomena of consciousness. Paradox. Silence. In my thirties I studied in San Francisco in a school which was a little hotbed of process theology. I read Whitehead and had my view of the universe upended. Back in New Zealand I didn't find anyone to talk to about this stuff, and it all kind of faded. I wrote a thesis based on a particular narrative theory: that of the tension between irreconcilable binary oppositions, (and gave workshops on story telling, and then found - ah, no! - all the underlying insight being subsumed under the entertainment value of my party pieces, Francis and the Wolf or She Who Sits Alone ).

And here in this book, I find all these many threads of my intellectual history being given a new home. They are called out, and integrated, and formed into a new whole with a new structure. I am so grateful. McGilchrist's emphasis is always on the gestalt - the wholeness - of the universe, which stands in opposition to our cultural predilection for deconstruction, that is for trying to break things down into continually smaller constituent parts. And it is all done so well.

Consider, for example, this small passage in which Process thought is so succinctly delineated:

Our troubles in this area, as in so many others, begin with the tendency to start from things, as though they were the important underlying elements in what we are looking at. Physicists have come to realise that the phenomena they are dealing with, though they may have some thing-like properties when viewed from a certain perspective, are better seen as processes. The 'building blocks' of the supposedly mechanical universe behave like patterned flows of energy, or force field: they are constantly moving and changing, have no precise boundaries, overlap and mingle with other equally elusive entities, cannot be precisely predicted or specified, change their nature and behaviour depending on context, including whether or not they are observed, and exhibit behaviour that defies any mechanical principles - for instance a 'particle' showing interdependency, or entanglement, with another too far removed across the universe for information of any kind to have passed between them. Matter it seems, is just, as Einstein confirmed, a particular manifestation of energy; not static and substance like, but constantly in a state of flow.

I am slowly working through the first chapters of volume 2, which are about The Coincidentia Oppositorum. Fancy that! My old narrative theory is held by a lot of brainy people, and has a fancy name, and it's it's even more subtle, profound and beautiful that I ever suspected. I will read slowly through this third part and get back to you, but in the meantime I will keep up my end of the conversation with that great process we call the Universe. I will make, and be made.

Comments