I arrive at the door, wondering if I have to pay admittance. I've never been an event photographer before and I have no idea what I'm supposed to do. The young woman at the desk looks up and smiles.

"Oh, we've been expecting you. Come in " she says. She stands and I follow her into the foyer where the show is set up. I put my large camera bag on a table and glance around. There are children everywhere, and someone in a rainbow costume is singing and playing her violin, and radiating seemingly inexhaustible energy from the small stage at the front.

"Rainbow Rosalind" says my host. "She's fabulous, isn't she?"

"Yeah. Great."

Who could argue? Who would want to? She's fabulous.

"Is there anything I can get you?" she asks. "Coffee? Tea? The friands are actually very good. "

"Ahh, no... I'm all good thanks. I'll just get on with it. OK if I put my stuff here?" She smiles and goes back to guard duty by the door. I pick a lens, fit a strap to my camera and walk tentatively down the side of the audience, trying to assess where the light is coming from, and nervously hoping I'm not getting in anybody's way. There's a couple of other photographers here. Their cameras look smaller than mine, more modern, more expensive, but mine has a certain gravitas borne of size and venerability. My compatriots and competitors glance at me and nod a cursory welcome. I nod back, trying to give the impression of nonchalant familiarity, watch them, and follow their lead.

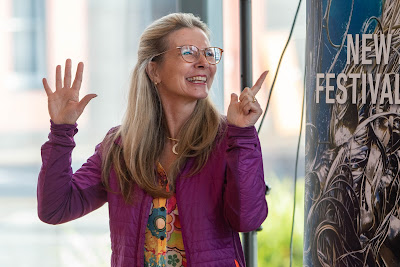

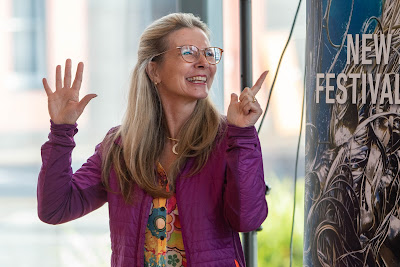

The star of the show is the incomparable Suzy Cato.

She does her well polished thing with a kind of relaxed exhuberance. I've been asked to get some shots of her, so I'm aware that I'm staring at her through my viewfinder for lengths of time, which in other circumstances might result in someone dialling 111, but she ignores me completely. As indeed she should. To her I'm as much a part of the furniture as the sound desk and the flood lights. The camera around my neck has rendered me completely invisible, and as I relax into that invisibility, I realise that pretty much everyone there is treating me the same way. In ancient China they used to use tiny jade screens to hide behind. For example if the guests arrived too early for dinner and you were still rushing around getting things ready you would put a little screen on the floor and people on both sides of it would pretend not to see each other. These things were only a few inches tall, but there was social agreement about what to ignore. And in our time, in our culture, a camera does much the same thing. I stood behind Suzy on her stage and no one reacted.

I got the shots that were asked of me, and I loved doing it. I loved being at a show I would never have chosen to attend, and I loved being invisible.

Because photography is the invisible art form. When I sent off my files, what people wanted was not me. They wanted pictures of the performers and the audience, and as long as my shots were in focus, and were well framed and well edited, and showed something of the energy and colour and life of the event, no-one could give a violinist's gaseous indiscretion about who it was that pressed the button on the camera. And as with this event, so, actually with all photography.

I take a lot of pictures and look at a lot that other people have taken, and there are a few things that really annoy me about some photos. Over enthusiastic editing for one thing, and twee little titles for photos for another. But what annoys me most is people putting electronic signatures at the bottom of their snaps, or maybe putting a digital frame around them, as though they are producing the darned Mona Lisa. Oh for goodness sake! Don't they get it? The photograph, not the photographer is the point of the exercise.

I carry my camera out into a cool Dunedin morning, and the job it does for me is to act as an aid to concentration. Even the fanciest camera is a limited instrument, and its many shortcomings force me to think about my own visual shortcomings: the manifold unconscious limitations to vision that I carry around in my head 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

The camera helps me see what is there. And once I've seen it, I take a photo in the hope that I can help someone else to see what was there. And it doesn't help them to see if I title the picture and thereby suggest their response, or if I turn a pretty reasonable picture into a crummy meme by plastering my name over it. My photograph is a kind of window, and I want people to look through it, not at it. I want to show you my city on a frosty morning, and the stillness of the water, and the colours, and maybe suggest the feel of what it was like to be there at that moment. I don't want to show you my camera or software. I certainly don't want to show you myself.

I have been taking pictures for a long time. I know exactly how good a photographer I am, and how good I am not. Of course I am always trying to get better, but I don't want to be thought of as a "good" photographer. I want to be an invisible photographer. I look out at the harbour through my living room window every morning, and very seldom think about the glazier, who did an excellent job and let in the light, thereby making my engagement with the harbour possible. Yep. Great role modelling there.

Comments